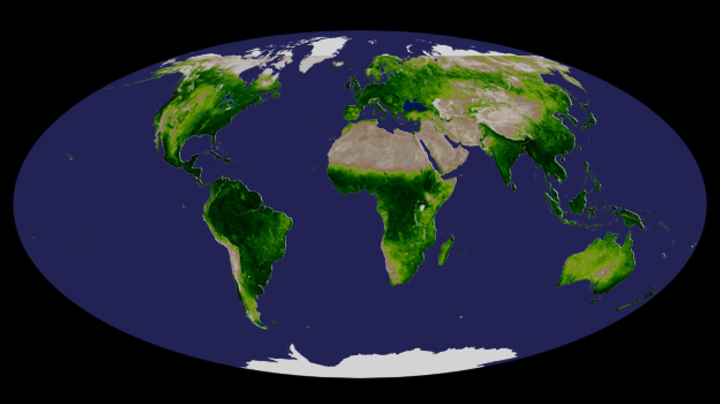

Shorebird populations are struggling to find wetlands on their epic migrations down the Pacific Flyway, stemming from Alaska and Canada down to South America. As water resources have decreased in the Central Valley of California due to development, agriculture and other land use changes, resting and feeding grounds for migratory birds has decreased.

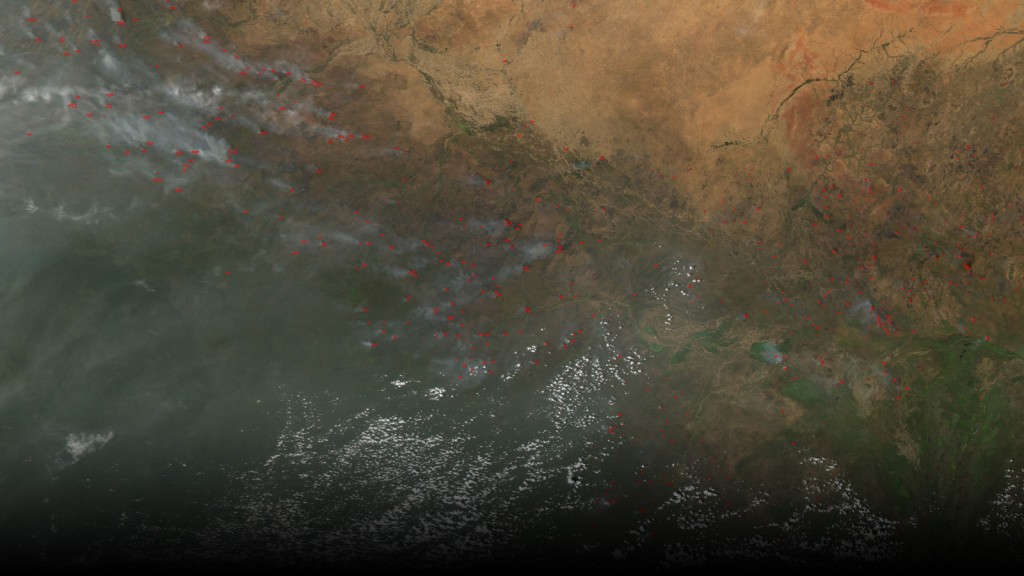

A team from Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s was able to use data from the Moderate Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on-board NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, along with data from Landsat to identify areas that could be turned into “pop-up habitats,” where rice fields could be flooded to provide temporary habitats for migrating birds for a couple weeks per year.

To identify areas that would be beneficial “pop-up habitats,” satellite data on the location and timing of surface water was matched with migration patterns of shorebirds collected from the eBird program, a citizen science bird watching program that collects data on bird sightings. The result is the BirdReturns program, a partnership between the Nature Conservancy and the California Rice Commission that compensates rice farmers to flood their rice fields at particular times to provide migratory habitat for shorebirds.

Efforts like this can help land managers better allocate valuable resources, such as water in California, where they are needed when competition for these resources are high.