CERES will be hosting the 29th annual CERES Science Team Meeting jointly with GERB and ScaRaB from September 10 – 13 at NCAR in Boulder, Colorado. The meeting will showcase scientific findings and plans for the studying Earth’s radiation and energy from space.

Past News

- December 2025

- October 2025

- July 2025

- May 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- April 2024

- February 2024

- December 2023

- October 2023

- April 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- October 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- April 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- November 2017

- June 2017

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- April 2015

- February 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- September 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

News By Instrument

News By Science

- Air quality

- Applications

- Atmosphere

- Carbon Cycle and Ecosystems

- Climate Variability and Change

- Data

- Earth Observatory

- Earth's Surface and Interior

- Education

- Energy Cycle

- Events

- Human Dimensions

- LAADS DAAC

- Landsat

- Orbital Changes

- Platform

- Resources

- Terra Talent Series

- Terra Visits Camp Landsat

- VIIRS

- Water Cycle

- Weather

- Wildfire

Tag: Energy Cycle

Energy Cycle News and Events

Study: Long-Term Global Warming Needs External Drivers

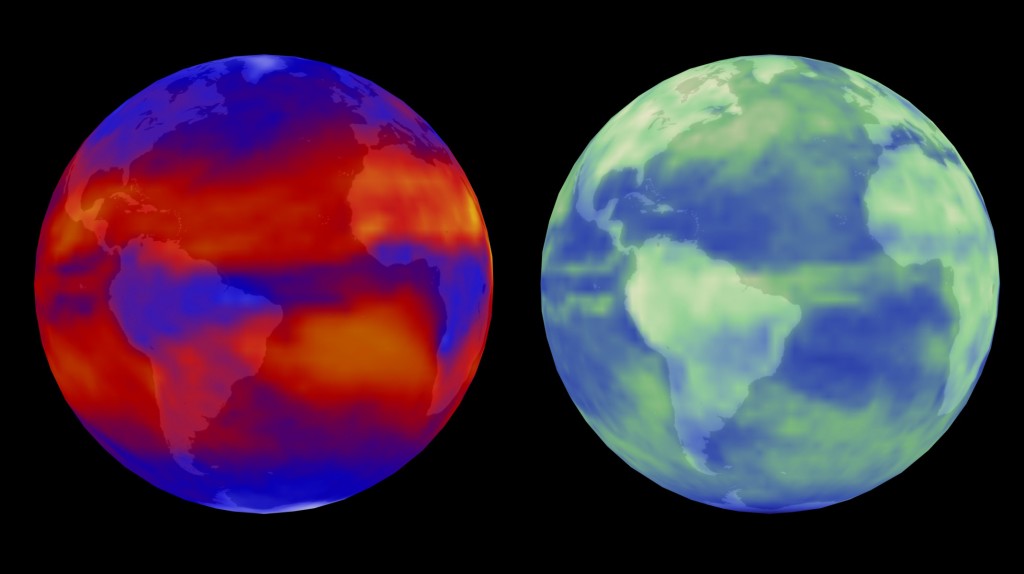

Terra/CERES views the world in outgoing longwave radiation (left) and reflected solar radiation (right). Image Credit: NASA

February 8, 2016

A study by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, shows, in detail, the reason why global temperatures remain stable in the long run unless they are pushed by outside forces, such as increased greenhouse gases due to human impacts.

Lead author Patrick Brown, a doctoral student at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, and his JPL colleagues combined global climate models with satellite measurements of changes in the energy approaching and leaving Earth at the top of the atmosphere over the past 15 years. The satellite data were from the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) instruments on NASA’s Aqua and Terra spacecraft. Their work reveals in new detail how Earth cools itself back down after a period of natural warming.

Scientists have long known that as Earth warms, it is able to restore its temperature equilibrium through a phenomenon known as the Planck Response. The phenomenon is an overall increase in infrared energy that Earth emits as it warms. The response acts as a safety valve of sorts, allowing more of the accumulating heat to be released through the top of Earth’s atmosphere into space.

The new research, however, shows it’s not quite as simple as that.

“Our analysis confirmed that the Planck Response plays the dominant role in restoring global temperature stability, but to our surprise, we found that it tends to be overwhelmed locally by heat-trapping changes in clouds, water vapor, and snow and ice,” Brown said. “This initially suggested that the climate system might be able to create large, sustained changes in temperature all by itself.”

A more detailed investigation of the satellite observations and climate models helped the researchers finally reconcile what was happening globally versus locally.

“While global temperature tends to be stable due to the Planck Response, there are other important, previously less appreciated, mechanisms at work, too,” said Wenhong Li, assistant professor of climate at Duke. These mechanisms include the net release of energy over anomalously cool regions and the transport of energy to continental and polar regions. In those regions, the Planck Response overwhelms positive, heat-trapping local energy feedbacks.

“This emphasizes the importance of large-scale energy transport and atmospheric circulation changes in reconciling local versus global energy feedbacks and, in the absence of external drivers, restoring Earth’s global temperature equilibrium,” Li said.

The researchers say the findings may finally help put the chill on skeptics’ belief that long-term global warming occurs in an unpredictable manner, independently of external drivers such as human impacts.

“This study underscores that large, sustained changes in global temperature like those observed over the last century require drivers such as increased greenhouse gas concentrations,” said Brown.

“Scientists have long believed that increasing greenhouse gases played a major role in determining the warming trend of our planet,” added JPL co-author Jonathan Jiang. “This study provides further evidence that natural climate cycles alone are insufficient to explain the global warming observed over the last century.”

The research is published this month in the Journal of Climate. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and NASA.

NASA uses the vantage point of space to increase our understanding of our home planet, improve lives and safeguard our future. NASA develops new ways to observe and study Earth’s interconnected natural systems with long-term data records. The agency freely shares this unique knowledge and works with institutions around the world to gain new insights into how our planet is changing.

For more information about NASA’s Earth science activities, visit:

Alan Buis

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0474

Alan.buis@jpl.nasa.gov

Tim Lucas

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

919-613-8084

tdlucas@duke.edu

2016-036

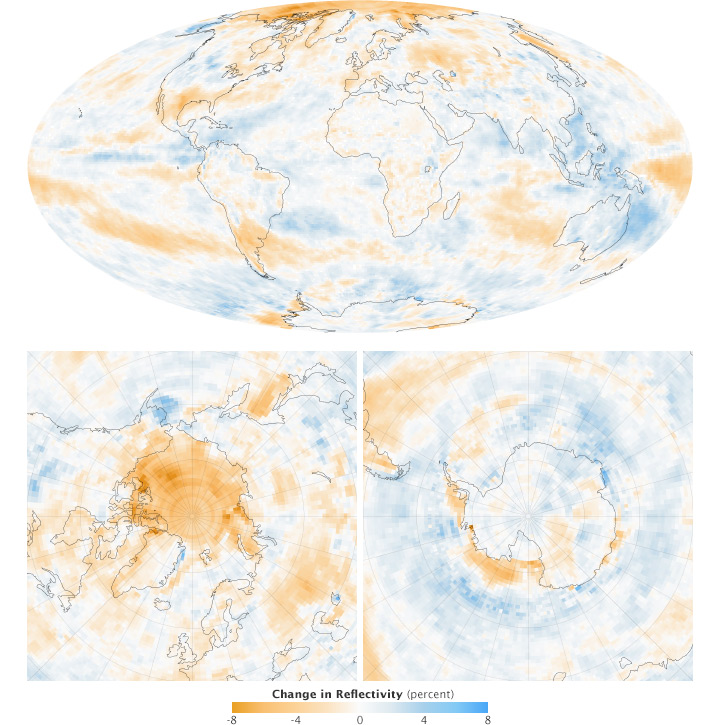

Measuring Earth’s Albedo

Sunlight is the primary driver of Earth’s climate and weather. Averaged over the entire planet, roughly 340 watts per square meter of energy from the Sun reach Earth. About one-third of that energy is reflected back into space, and the remaining 240 watts per square meter is absorbed by land, ocean, and atmosphere. Exactly how much sunlight is absorbed depends on the reflectivity of the atmosphere and the surface.

As scientists work to understand why global temperatures are rising and how carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are changing the climate system, they have been auditing Earth’s energy budget. Is more energy being absorbed by Earth than is being lost to space? If so, what happens to the excess energy?

For seventeen years, scientists have been examining this balance sheet with a series of space-based sensors known as Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System, or CERES. The instruments use scanning radiometers to measure both the shortwave solar energy reflected by the planet (albedo) and the longwave thermal energy emitted by it. Read more

NASA-led study solves case of Earth’s “missing energy”

Two years ago, scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., released a study claiming that inconsistencies between satellite observations of Earth’s heat and measurements of ocean heating were evidence there is “missing energy” in the planet’s system. Where was it going? An international team of atmospheric scientists and oceanographers, led by Norman Loeb of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va., and including Graeme Stephens of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., set out to investigate the mystery. Read more.