The excellent health and longevity of the Terra platform and its five instruments has led to the enviable problem of deciding how best to manage fuel usage of the platform over the next five years. The decision will directly impact both the continuity of the Terra science record and the length of time that Terra will remain on orbit. The Project is looking to better understand the possible benefits to the science community from different fuel use scenarios and welcomes feedback.

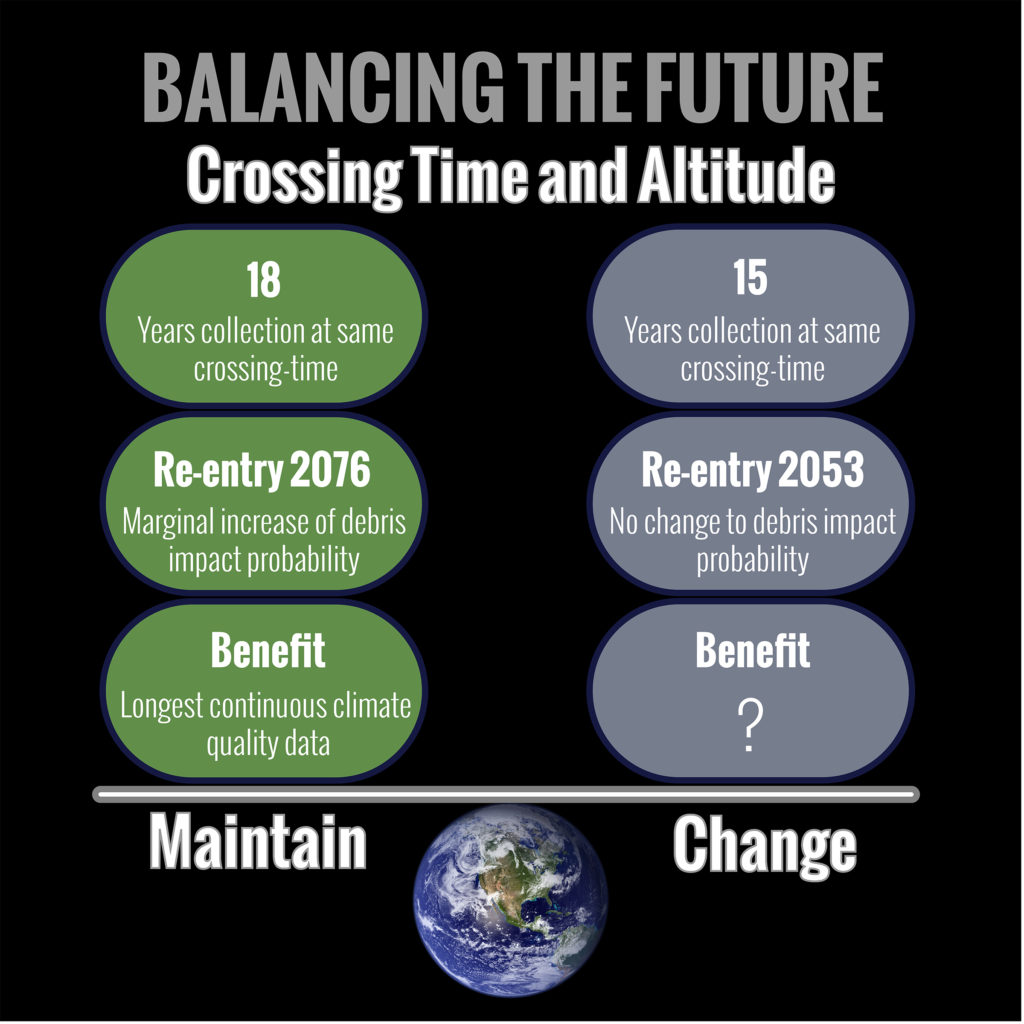

The question that poses itself now is whether to use all of the remaining maneuvering fuel to maintain Terra’s current orbit and keep the equator crossing-time at 10:30 AM (within a tight time window of 10:29 AM to 10:31AM local time) which will lead to nearly 3 more years of continuous climate quality data or to use some of the fuel to lower the orbit leading to an earlier re-entry of Terra. The earlier re-entry decreases the probability that Terra will be impacted by space debris, although all orbiting satellites are at risk of being hit by debris and rely on collision avoidance maneuvers to minimize this risk. Terra will maintain fuel reserve to perform these maneuvers after lowering or exiting the constellation to minimize risk of collision.

A major impact of lowering Terra’s orbit is a change in its crossing time. A body of scientists acquainted with Terra’s instruments concluded that a “change in the crossing-time would mark the end of Terra’s ‘climate quality’ data record for trend analysis”. The panel stipulated that the magnitude of the impact would be of the same order as the trends projected by climate models. The fact that Terra still has five healthy instruments providing a continuous well-calibrated, inter-calibrated, data record led the panel to conclude “that it is of utmost importance to continue this data record while the Terra instruments are performing nearly optimally.”

In order to provide a data set of the best quality for the science community, the Terra Project Science Office, including the five instrument teams, recommended that the current crossing-time be held until fall 2020. Doing so, would sustain an equatorial crossing time within a two-minute window for an unprecedented 18 years while still allowing a safe exit from the Earth Science Constellation. The use of fuel to maintain Terra’s crossing-time until fall 2020 leads to a predicted additional 18 years on orbit and a corresponding marginal increase in the probability of a debris impact. The science possible from a near-constant crossing time for 18 years is unique and viewed to offset the added risks involved from the additional time on orbit. What is not clear to the Terra Mission, however, is whether there are science applications that would benefit from either a shift in crossing time or an orbit lowering. The Project is currently searching for possible science benefits from the orbit lowering and plans to hold a panel discussion at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting in December, 2017.

The Terra Science Team welcomes any feedback or suggestions as to whether to maintain the current orbit and the long-term data continuity, or lower the orbit, and therefore, shifting the crossing time.

** Note that Terra did not come to maintain a consistent 10:30 am crossing time until 2 years after its launch.

Please leave any feedback or suggestions by contacting us. All comments will be considered in our panel discussion on December 10. Comments left after December 10 will be considered prior to Terra’s next planned inclination maneuver.

Contact us – Your feedback is important

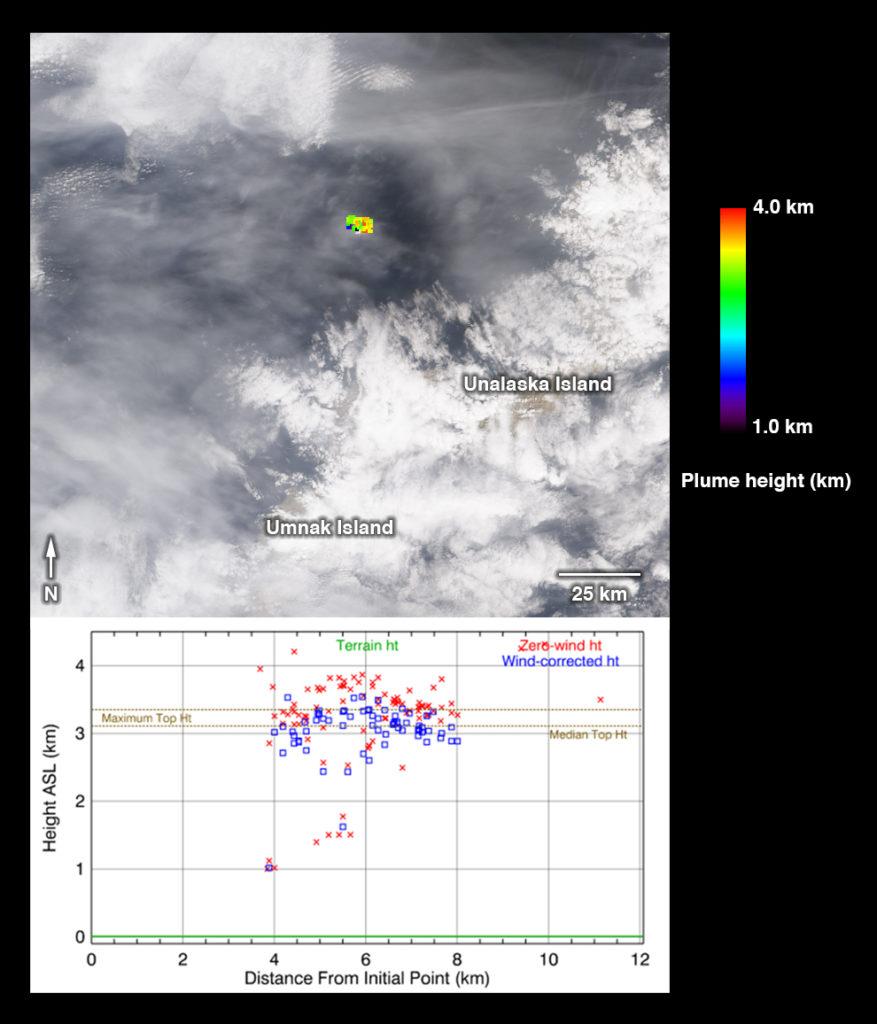

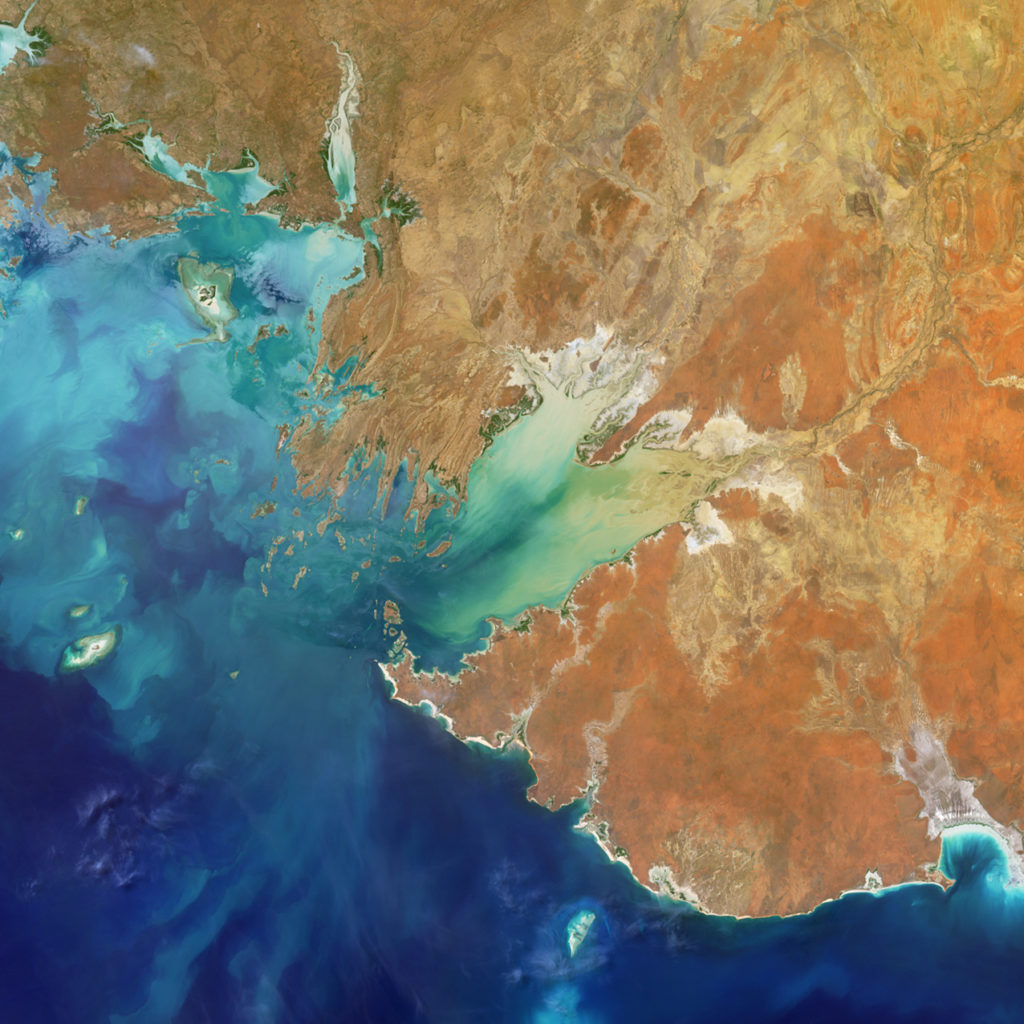

Are you ready for a challenge? Become a geographical detective and solve the latest mystery quiz from NASA’s MISR (Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer) instrument onboard the Terra satellite. Prize submissions for perfect scores accepted until Wednesday, June 28, at 4:00 p.m. PDT. Happy sleuthing!

Are you ready for a challenge? Become a geographical detective and solve the latest mystery quiz from NASA’s MISR (Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer) instrument onboard the Terra satellite. Prize submissions for perfect scores accepted until Wednesday, June 28, at 4:00 p.m. PDT. Happy sleuthing!